I spent the past week staring at my own breath. Walking to and from the subway in the coldest weather I can remember, a fifteen-minute journey that somehow manages to be uphill both ways, I use my exhalations as a kind of thermostat, the way you count cricket chirps in the summer. I see my breath as proof that I’m justified in my suffering, proof that the weather is doing its job.

Despite my misery, I experience a childlike amusement when watching my own breath. Since I lose every pair of gloves, my hands end up tucked into my coat pockets, forcing me to look at something other than my phone. Observing my surroundings is never enough—I need to feel like a part of them—so I breathe out. My exhalation blurs the city, filling the gaps between buildings, as if my presence is as integral to this place as everything else. It disappears quickly. But for a moment, the cold feels like something I can control. I wonder if the other commuters feel it too—that small, ridiculous joy in watching their own breath drift in front of them, the quiet acknowledgment of the season’s cruelty and their place within it. But then, inevitably, the thought arrives: They probably just think I’m a mouth breather. And so I stop.

I am, at least, somewhat photosynthetic. I grew up in a town halfway between Los Angeles and Palm Springs, where winters rarely dipped below 50 and summers regularly cleared 100. I spent my childhood running barefoot across asphalt so hot it could fry an egg, moving fast enough to feel the burn without letting it catch me. This was how I navigated the world: lightly, quickly, skimming over its harsher surfaces.

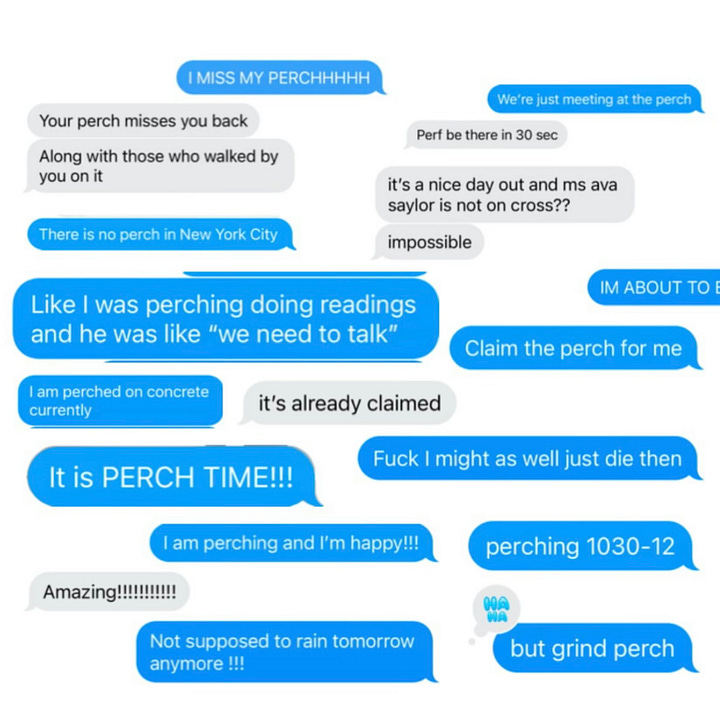

There’s a strange relationship between the weather and my emotions, which only amplified after leaving California. When I moved to the East Coast at eighteen, I gained a reputation as the girl who sat outside. Any sunny day above 50 degrees, I’d be on a concrete slab in the middle of campus overlooking the main lawn. My friends would joke, “If you can’t find Ava, she’s on her perch.” And I always was. I had learned that the sun was not a guarantee, and truthfully, I missed it. So, I cherished the light I could get.

Perching wasn’t just about basking in the sunlight. It was an opportunity to watch friends pass between classes, to share quick stories and to-do lists, to–on occasion–convince them to sit alongside me. My favorite days, though, were the ones following a stretch of rain or cold, when the masses descended on the lawn and stuck around, as if they’d just realized how easily warmth could be stolen. I’d watch them play frisbee, read tarot, blow giant bubbles that seemed to leave the atmosphere entirely. The sun lifted my spirits, but the life surrounding me ignited something deeper, something that fueled me even as the seasons started to shift. It made the cold concrete I sat on feel like the asphalt back home. Put simply, warmth makes me happy, and happiness makes me warm.

Like most people, I slow down when the temperature drops—less energy, less motivation, less optimism. The days shrink, and so do I. But I’ve realized it works both ways: While I am inconsolable in the cold, I’m also cold when inconsolable. Loss, heartbreak, difficult conversations—they drain the warmth from me just as reliably as winter does. Winter makes me sad, and sadness makes me winter.

My first East Coast winter was unforgiving. In California, winter was a few leaves falling and the mild discomfort of a long sleeve under your hoodie. In Connecticut, winter announced its arrival with a nor’easter, a word I’d never heard but now associate with winds that cut through your coat, your sweater, your skin, your joy, and keep going.

I wasn’t just cold that first winter; I was alone. Most of my new friends had moved away for the semester because of the pandemic. I didn’t call home as much as I should have. The loneliness settled in my dorm room, which felt like an abandoned sleepaway camp—seven empty beds, one occupied by me. I spent hours hunched over my guitar, pressing calloused fingers to metal strings, sitting as close to the heater as I could. It didn’t help. Nothing did—not even spring, when the days finally stretched out and the air softened. I took longer to thaw than the rest of the world.

Lately, I’ve been feeling cold again. Not just the kind that settles in your bones when winter drags on too long, but the kind that fills the spaces between people, the one that wraps itself around you when the world doesn’t reach out. It’s a chicken-and-egg situation, really. The cold keeps me inside; the more I stay inside, the colder I become.

I truthfully think that my postgrad “I’m a real person now” adjustment period is the main source of this mental wind chill. Whenever I begin to think about the friends I haven’t seen in a while, or the lack of decoration in my studio apartment, or the fact that I live alone in a studio apartment, or the fact that I live on the other side of my country from my aging grandparents, or the fact that we are all aging, or the general direction of my life and the billions of lives around me and the questions that trail us all, I begin to shiver, pile on sweaters, bury myself in blankets. It’s as though my body, betrayed by my emotions, has found its own primitive defense: shutting down, pulling inward, conserving warmth I can’t seem to find. I get cold.

And that’s just in my head. Outside, there’s a sharpness, a loneliness in the way people move—quick, without eye contact, pushing past each other like they’re all running out of time. Things feel hollow despite being full; you pass bodies without meeting anyone’s gaze. I feel the temperature change in the silence of my apartment, in the incessant noise outside, in the weight of the days that stretch, indifferent, ahead of me. I wait for the sun.

I’ve been on the East Coast for almost five years now. I’m happy here, but I joke that it feels like a veil lifts whenever I return to California—like, oh, this is what happiness feels like. It’s warm, it’s easy, and you forget what it was like to not have to work for it. But here, in New York, I feel that winter reveals the worst parts of ourselves. The brusqueness, the sharp edges, the indifference of people who won’t meet your eye as they shove past you. It’s the coldness of a place where survival depends on the ability to be unbothered. I’ve learned to keep my head down, to move just fast enough to avoid being hurt—a skill I perfected years ago under a much hotter sun.

But then there are the moments—a song perfectly sad enough for the weather, my cheeks flushing a red people would pay for, the sight of my own breath—that make me smile. The many indicators of a bad day have turned into something I eagerly anticipate. I relish the rituals: endless batches of soup I won’t finish, loaves of bread left to gather dust because I keep baking more. The vitamin D pill, always on the countertop, rarely taken. The weekly Bachelor watch parties, meticulously planned and hosted. The books I read, the books I just acknowledge. The mess, the half-hearted cleanup that never quite takes. I’ve found something in this cold.

Much like my first winter here, I consider myself more creative when the chill sets in. There’s a kind of starkness to it, an emptiness that’s supposed to leave room for clarity. It’s no wonder Bon Iver holed himself up in a cabin in Wisconsin to record For Emma, Forever Ago—the cold strips everything down, gives you space, in a way the warmth never can. So, I write. I sing. I start knitting and candle-making and ballet—all things that prove unsuccessful. When it’s cold, failure feels like something different, as if the very fact I’ve tried anything at all is enough to say I’ve succeeded.

The cold lets you get away with so much. I show up to my office in purple Uggs, and no one questions it. I let myself sleep in longer, light every candle in my room to test how long it takes to go nose blind. The cold gives permission—permission to slow down, permission to indulge. The cold doesn’t ask for much in return. It’s a little absurd how easy it is to surrender to it.

But it’s not all surrender. The cold also lets you get away with little. There’s the humiliating scramble to stand after slipping on ice, the frustrating battle to turn an umbrella back the right way after it’s been twisted inside out by the wind. The cold has a sense of humor—sharp, dry, unrelenting. No one notices the subtle changes of the sun, day after day. It’s the cold that holds your gaze, even as others won’t.

The cold makes you notice the little things. The dad with the sled over his shoulder, the way his kids race ahead. The “it’s snowing!” that echoes in the office as coworkers gather by the window, peering out into the white. The person across the street, their breath forming clouds in the air, dissipating as fast as they appear. Are they just as easily entertained? Maybe it’s unintentional, or maybe they’re also wondering if I’m noticing them, if anyone is noticing anything at all. For a moment, I feel less alone, less like a mouth breather choking down the cold.

Love the superpuff <3

🤞🏻sunny skies and warm temps find us in a couple weeks!